Meeting the Masai

In the midmorning of our third day on safari, when the heat was just starting to get so intense you figured you’d die without shade, we hopped in the car and headed to a Masai village for a visit. We had been warned that many people find the visit disappointing, as it’s so touristy and commercialized, but I think we enjoyed it.

The guys came out of the manyatta to dance, one sporting a tall lion’s mane hat (ostensibly because he had been the first to throw the spear at a lion on a man-making hunting trip) and another blowing out a rhythm on a curled gazelle’s horn. The others, resplendent in wigs and beads and brilliant red wraps, sang and jumped and jogged. Jumping is a sort of competition, our guide Jonah explained. Whoever jumps highest is likely to get the girl.

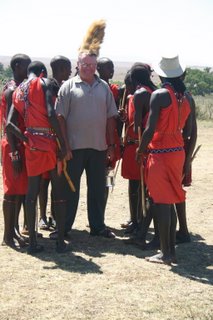

At one point, they encircled Dad, removed his hat and replaced it with the lion’s mane and danced and sang around him. They gave Mom the same treatment and they both had the good graces to smile for pictures. Emily beat a hasty retreat, spying some dirty, raggedy children watching from nearby, worried they might encircle her next.

When we entered the manyatta, the women were lined up. Their heads were shaved, their ears were elaborately decorated, they were dripping in beads and wrapped in brilliant scarves. Their wrists and ankles were covered with beads. A few carried babies on their backs. They sang for a while, then gathered up the women to sing with them and then “shook” hands in the manner of competing baseball teams at the end of a match.

Then Jonah and the boys showed us how they light fires without matches and then we headed inside one of their homes. The kids had gathered around by that point and, my oh my. There was just no excuse for how dirty these kids were, considering that tourists pay the equivalent of $10 each to visit their homes. The last time I saw kids this raggedy and unkempt, it was in poverty-stricken Mali, where there is barely enough water to go around, so the kids live in dirty rags. There was no explanation as to why these kids weren’t in school, or even whose kids they were. (The driver said later they belonged to the young boys who led us around.)

Once inside the home, we started asking questions. The home itself was made of cow dung mixed with a few other things and dried in the sun. It was stuffy and claustrophobic. Jonah pointed out the beds, which were narrow strips of cow hide, and the cooking pit, which was a triangle of charcoal in the centre of the floor, and the “windows” for ventilation, which were two tiny slits on the walls. It was roughly 4,000 degrees inside the house, yet Jonah assured us that there were lots of Masai blankets around for when it got cold at night.

He told us that Masai are polygamists, so each man can take up to 10 wives and he must keep them in their own houses. Their children live with the women until they reach a certain age, then they often go live and work with other families, or go out to tend sheep or cattle. Each boy is given his own herd by his father. The father decides who he will marry. They’re circumsized around 16, after an elaborate week-long celebration in the bush, in which they’re separated from their families and expected to hunt a simba lion. They can marry at 24 and each of the boys leading the tour were just under that age. They told us the fees charged to enter the village went to taking care of the elderly, paying for medicines and hospital bills and paying school fees and for books and things. Yet still, they admitted that in each family, usually only one child goes to school, while the others go to the fields or work around the manyatta.

At the end was the Masai equivalent of visiting the gift shop, a circular open-air market where they sold the same crafts, beadwork, necklaces, sculptures and blankets at table after table. I found there wasn’t much room to bargain and walked away empty handed, but the parents surprised me and bargained for a few necklaces.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home